Keele - On writing

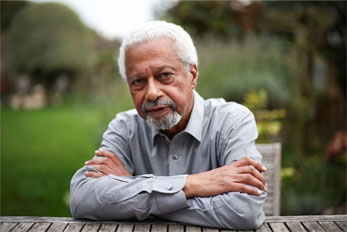

Source: Reuters/Alamy Stock Photo/Henry Nicholls

It’s not often I find myself in awe. However, on my first visit to Keele in the spring of 2023, my lips parted and legs weakened slightly at seeing Keele Hall creep out of the early morning mist. It was in this same building, nearly two years later, where we now sat.

On Wednesday, December 11th 2024, Keele welcomed professor Abdulrazak Gurnah for a public reading in the Westminster theatre. Beforehand, Mr. Gurnah graciously agreed to a private Q&A session with Keele’s Creative Writing students and staff. This was a uniquely excellent opportunity to gain knowledge from one of the greats. As we awaited Mr. Gurnah’s arrival, the air was thick with anticipation: palms were sweaty. A meeting of this caliber is, as they say, ‘once in a lifetime,’ and the pressure to make the most of our time with Mr. Gurnah was on everyone’s mind.

When our guest finally arrived, pleasantries were shared and smiles exchanged. There was however, the overwhelming sense of his presence. I’m not quite sure what it was: the way his eyes seemed to absorb the room entirely, his seemingly calculated movements, or maybe it was nothing more than a mental placebo. What I do know is that we were all in awe.

Mr. Gurnah slowly took his place at the front of the room. The Q&A that follows is recorded here, paraphrased, with a bit of added context into Mr. Gurnah’s history, career, and literary successes. We, the writers, held on to every moment of our time with him, and we can’t thank him enough for his generosity and insights.

Abdulrazak Gurnah was born in 1948 in the Sultanate of Zanzibar. His early childhood was backdropped by economic and political turmoil, which forced him from his home and to the UK as a refugee in the 1960s. His experiences during this time inspire much of his writing, and give his work the honest privilege of being inspired by experience. With this in mind, our Q&A began.

Do you write because you understand these things, or because you want to understand them?

Write what you know, but don’t limit yourself to only your experiences. Writing what you know can include the thoughts and stories that other people have shared. These can be things you’ve read or watched in creative media or through the news. However, writing about these things only works if the ideas and emotional reactions to them are internalized.

How does research insert itself into your writing process?

Background can always be researched, but the characters and their feelings cannot. What’s most important when writing a tale that has a specific historical backdrop is that the characters exist apart from the world -they are entire beings separate from their environments. If you need details in order to add descriptions to setting or specific events, that can come later in the story-building.

Do you have a question in mind when you write?

It’s not necessarily a question that starts a novel, not something that needs to be answered, exactly, but an idea. If anything, many stories are a way for authors to answer personal questions, rather than ones for the reader to answer. As a writer, you must have confidence in your ideas and the things you feel need to be said about the world.

After emigrating to the UK, Mr. Gurnah earned a degree from Christ Church College before receiving his PhD from the University of Kent in 1982. After receiving his doctorate, Mr. Gurnah became a lecturer at the university in English and Postcolonial Literature until his retirement in 2021. Our next questions were based around the physical process of Mr. Gurnah’s writing that eventually led to his success.

Where do you write?

I’ve written in many different places. I used to write quite a bit on a chair in the living room, notepad propped up again the arm. However, over time I’ve shifted towards technology. At first I used a typewriter, then moved to an Amstrad which always took ages to boot up and made a terrible whirring noise. I now write my manuscripts, like most, on a computer. When I’m out on the train or in the car, I’ll occasionally write something down in a notepad, but it doesn’t feel like a complete piece of writing until it’s found its way digital.

What is your writing schedule?

It depends on the length of work. Novels often require several months to be written fully, and I like to know that I have a set amount of time when I won’t be distracted by other big projects. However, it’s also okay to write small pieces and put them away for a while. For one novel I wrote the last chapter first and put it away for a few years before eventually revisiting it and using it in a longer piece of prose.

How do you find a writerly voice?

Finding a writing voice isn’t something that’s done mechanically, through word choice, for example. Instead, it’s like music in the way that it flows naturally and is a part of the writer’s toolkit. It’s a distinct style that is built up over time and practice.

Thanks to his work, Mr. Gurnah earned the prestigious Nobel Prize for Literature in 2021. In his official Nobel Lecture, he pondered on how reading and writing became a pillar of his life so displaced by turmoil and unrest. If you have not had the pleasure of watching this lecture, I would highly recommend it.

In addition to the Nobel Prize, Mr. Gurnah has been featured on multiple Man Booker lists, for his works Paradise and By the Sea. He’s received numerous accolades and achievements in similar book prizes around the world. This is what inspired our final question.

With receiving such a prestigious award [the Nobel], has writing changed in meaning for you?

No, writing fundamentally, for me, hasn’t changed in purpose. In the world of writing there are two different kinds of recognition: awards and readership. Writing will always be for people to read, and the awards merely help convince people that certain words are worth reading. However, the awards certainly do bring a lot of attention, so now I often find myself distracted from actually writing by all the prestige.

Once again, we at Keele are incredibly grateful for Mr. Gurnah and his time spent with us. Having the opportunity to engage with masters of the craft is one of the most valuable resources in any art, and Mr. Gurnah’s expertise is matched by few. Thank you additionally to Professor Mariangela Palladino of Keele for helping organize and run this event, and to Keele Hall for providing the venue.

If you’re interested in attending future Keele Hall Readings, please check out our semester 2 program.

Rachel Seiffert is the award-winning author of four novels. Her career has included high profile recognition fromthe Guardian First Book Awardand the Booker Prize. In 2003, she was named one of Granta’s 20 Best Young British Novelists.

In May, Keele Hall Readings was fortunate enough to welcome Rachel into a reading of her new novel, Once the Deed is Done, as well as a Q&A. Beforehand, we sat down to discuss her 2001 novel, The Dark Room, along with her writing process. The following answers are paraphrased from our discussion.

Where did the inspiration for The Dark Room come from?

The original inspiration came from my family’s history. My grandparents were Nazis who were taken into Russian captivity during the war. This formed the latter of the three novellas. The other two were heavily researched.

What was that research process like?

I grew up with stories of the war and my grandparent’s role in it. My family never tried to hide our history, which was important for me in being able to understand their lives. I would also read perspectives from both sides of the fighting, not to justify one over the other, but to better understand. It was through this reading and my familial exploration that I realized the people you love are capable of awful things.

What was the reception like apart from the big awards?

The book was first published in Germany. Whereas the English release would go on to critical recognition, the response in Germany was much more sustained. These stories helped German people reconsider the war, and confront their own family’s involvement in it, much like my own.

I then turned our discussion to the craft of writing itself. Although each writer’s process differs, it’s still fascinating (and potentially helpful!) to hear what writing looks like for different authors.

What is your writing schedule?

I’ve worked as a writer in residence and have served as a Royal Literary Fellow, but I try to keep my writing schedule consistent. I aim to write 3 days per week, aiming for 500-1,000 words per session.

Where do you write?

Seemingly everywhere: in bed, at the kitchen table, but never in my office. When I walk my dog, I often carry a notebook to jot down ideas. While writing, I always have a knitting project in my lap, I’ve found the physicality of knitting helps keeps my brain moving, allowing me to think.

How do confront writer’s block?

Simply, write and sit it out. I often rewrite some sections of a project if I feel the story’s not going in the direction I’ve intended. Also, don’t be scared to write scenes out of order. If a specific chapter or moment excites you at the time, don’t worry about the chronology of your process.

I then thought to Rachel’s novels: to deep investigations of human choices, philosophy, and courage set in turbulent historical settings. This inspired my final question.

What would your advice be for new writers who want to write with purpose?

There is a space for writing that is cozy, but I write because I want to understand. I want to know why things happen; answers that emerge as much in the research of writing as it does in the writing itself. The key is to drop characters into tough situations, then write the emotional reactions that follow. I’ve learned throughout my writing that fear often looks like bravery.

A huge thank you to Rachel for taking the time to speak with me. Click here if you’re interested in future Keele Hall Readings.

Writing short is hard. Writing short fiction with coherent characters, setting, and plot is even harder; so I went searching for advice. Who I found was Chris Cottom, from Macclesfield, who’s been writing short fiction seriously since he retired in 2018. Since then, his stories have appeared some 140 times in places like 50-Word Stories, 100 Word Story, Eastern Iowa Review, Fictive Dream, Flash 500, Flash Frontier, Leon Literary Review, Oxford Flash Fiction, Oyster River Pages, Roi Fainéant, Streetcake, and The Lascaux Review. He’s won competitions with 3-Minute Arts, Allingham Festival, Cranked Anvil, Free Flash Fiction, Hysteria, National Flash Fiction Day NZ, On The Premises, Pokrass Prompts, Retreat West, Shooter Lit, WestWord, and others. The following Q&A dives into Chris’ own writing routine, and offers insights into how we, as writers, can begin to approach writing short fictions.

Step 1: The Idea

Where do your ideas come from?

This, for me, is the hardest part. Most of my ideas come from reading world-class short fiction. I save online stories I like or find interesting, or tick others in anthologies, particularly the Best Microfiction series, returning to my favourites again and again. Any story, title, phrase, or single word might prompt a theme, character, structure, format, setting, or mood. I’ll often try and collide something from one such story with something from another, or with a memory.

How do you decide whether an idea is better suited as flash fiction or as a longer piece?

I only ever set out to write to a particular length if I feel inspired by a particular competition or submission prompt, and that rarely happens above a 100-word limit. My stories don’t grow over 1000 words very often, and only when the characters won’t leave me alone.

When do you know a story idea is worth pursuing?

When the third cup of tea is growing cold in the teapot and I have a pain in my side from not going to the loo because I simply can’t stop pouring the words out.

How do you deal with writer’s/idea block?

For a long time it’s been by mooching around in a bad mood because I can’t think of anything to write about, no matter how much I trawl my favourites. I’m learning to let ideas meld, to trust a part of the process that I can’t understand, to allow disparate ideas, characters and phrases to jostle in my head before I go to sleep, when I wake through the night, or in the half-awake zone before getting up. Just this week I spent all Monday bouncing an idea around my head, but this time I accepted that it wouldn’t settle. When I woke on Tuesday, my way into the piece was clear and I sat down to write. About four hours later I got round to having a shower and cleaning my teeth.

Step 2: The Writing

What does your writing schedule look like? How do you feel about the ‘write every day’ adage?

I’m not sure that the adage is particularly helpful. Lots of people have to work, care for others, collect stamps, etc. But since I’m lucky enough to be retired, for me it isn’t a schedule, it’s a life. In his book Henry Miller on Writing, the great man said, ‘Write first and always. Painting, music, friends, cinema, all these come afterwards.’ Sorry, Henry, I quite like going to the cinema, but I do generally write every day, even if that’s only fiddling with commas, or reading a piece yet again before submitting it. And I spend lots of time giving written and verbal feedback on other people’s work, as well as doing a fair bit of writing and editing for the busy church which I’m part of: web pages, leaflets, funding applications and appeals, recruitment packs, agendas and minutes, etc.

How much do you research for your stories? Do you research before or while you write?

I can happily lose myself on the internet, convincing myself that I can’t possibly start writing until I’ve read every last word on flatweave carpets or the death of Galileo. But I usually research as I write, or sometimes I’ll put an ‘X’ to fill in later with the colour of a 1967 Triumph Herald, a type of Swedish bread, or a West Country variety of dessert apple. I’ve learnt to save the sources in case I want to change Wedgwood Blue to Litchfield Green, or after a Swedish friend tells me they might eat lingonberry jam with porridge, but never on bread.

Step 3: The After

What does your editing process look like?

Writing is rewriting. Nothing is ever finished. Alice Munro famously tweaked already published stories for republication in further collections or anthologies. So I’ll go on fettling forever, right up to a deadline. I’ll try to do the following, for every piece.

- Read my work aloud, again and again, obsessing about rhythm and internal rhyme.

- Remember my father quoting a famous author’s advice to write three words and cross two of them out (unfortunately I haven’t been able to attribute the source).

- Search for further redundancy, for places where I’ve failed to trust the reader, for smartly phrased darlings I must force myself to kill.

- Use this text analysis tool to show me words and phrases I’ve repeated, like describing two unrelated items as purple.

- Use this thesaurus to find that better word.

- Rarely submit anything without receiving feedback from several peers.

- Let my work simmer, coming back to it day after day, adjusting the seasoning, turning up the heat.

What would be your advice for people entering short fiction competitions?

- Where possible, read the winning and placed stories from previous competitions. Personally I generally avoid competitions where these aren’t easily available.

- Where possible, read judges’ reports from previous competitions.

- Where possible, read published work by the judges.

- Make sure your story is ready. Don’t be in too much of a hurry. There’s always another competition.

- Read the terms and conditions very carefully. Read them again.

- Pay very careful attention to formatting requirements. Don’t blow your chances for that fabulous piece by using Times New Roman 12 when the competition specifies Arial 14.

- Consider your expectations. If you regard a longlisting as a win (and I suggest you should), maybe you want to look for competitions which have longlists of 50, rather than those which go straight to shortlists of six.

- Track what happens. Count your successes. If your story doesn’t make the cut, enter it elsewhere. I entered my story How to Make a Dad Quilt into six earlier competitions before it won The Phare’s Flash Dash Competition.

A huge thank you to Chris for offering his insights into the craft of writing. If you’d like to read more of his work, you can find relevant links on his website as well as on Bluesky: @chriscottom.bsky.social

Jo Bell is a poet and author from Sheffield whose work spreads across form and content. After growing up adjacent to the Peak District, she became an industrial archaeologist, eventually working to preserve some of England’s oldest canal boats. Her newest work—a memoir and history called Boater: A Life on England’s Waterways—explores this often-forgotten side of England’s landscape. Before her recent Keele Hall Reading, I was fortunate enough to sit down with Jo to discuss the challenges of writing a piece of Creative Nonfiction (CNF), along with practical advice for new writers looking to improve their craft.

The following Q&A is paraphrased.

What do you think makes for a good memoir?

Getting your ego out of the way. The story may be about the writer, but if that’s all it is about, then it will be boring. It has to offer the reader a feeling of solidarity; it must stand for something, or else just be a bloody good story. It’s often at its core a spiritual journey. It’s possible to write a story about a perfectly ordinary life, but when put in the hands of a good writer, even that can become much larger than the sum of its parts.

How do you deal with the psychology of writing CNF? Sharing your private life?

It’s important to separate the writerly self from your actual self. I think it’s also important to only write about things that you’re able to write about with a bit of emotional distance. Bear in mind that the story you want to tell now may have repercussions for other people, which you might regret ten years from now. The main responsibility you have is to the future you.

How often do you think about readership in your writing? Does that impact what you write?

I think it’s unhealthy in any kind of writing to try and anticipate what the reader wants. You write what you want to write, especially in the first draft. Then seek constructive feedback to make sure it’s coherent and engaging, but don’t try to second-guess what an imagined reader wants. Once you’re at the final manuscript, the publisher will have input too; nonetheless it’s your story, and in the case of memoir that is literally true.

How do you balance the creation of a narrative with factual accuracy? Do you feel a certain responsibility in writing people and places?

Memoir fundamentally, is a sliding scale between truth and accuracy. You must tell the truth, but not all of it and not necessarily in the right order. You might leave out things that happened because they don’t help the story along – or you may paraphrase a conversation to give the gist of it. As for responsibility, yes. Your writing could have real implications for other people’s relationships, their jobs, or their sense of self. What you can’t do in non-fiction is to actually make stuff up. That’s fiction. ‘Creative’ in this context does not mean ‘licence to lie. It means that you can include poetry or other media, you can mess about with the chronology or the perspective, you can interject or interrupt your own story.

How do you filter feedback from others? When do you know to leave a comment out of your edits?

Input from trusted readers is a gift, and only a bad writer is reluctant to hear it. You must always expose yourself to feedback, and you must also give feedback; these are the quickest ways to improve your craft. All constructive feedback is useful, especially if it’s something you don’t want to hear. It may spark a question as to why somebody read your piece a certain way, and whether your story actually works. For instance, honest feedback from other writers will show where your brilliant narrative structure just confuses the hell out of a reader. Listen to them. But it’s also important to have your own discretion. You know your story best, and what it needs to say.

Any other advice for aspiring writers in CNF?

The main work of the writer is to walk through the world paying attention. Put down your phone, take out your earbuds, and pay attention. But if you do nothing else as a writer, you need to read. Read a vast range; things you enjoy, things you don’t. Read like a writer, not a fan. Observe how a writer is engaging your emotions, what they are doing with the structure and how they use language.

Thank you so much to Jo for taking the time to speak with me. If you’re interested in reading her new memoir, Boater, you can find the link here. Jo also founded a creative community called The Poetic Licence, an online poetry village based on a long monthly poetry prompt and the sharing of constructive feedback. You can find out more here.

You can also find Jo on Instagram @Jobellboater