A Guide for the Childe and Youth

Archives work placement

I’m Ashleigh Coffey, a master's student (2020/21) in History at Keele University. One of my modules gave me the opportunity to do a work placement in a related field and having previously volunteered at the Grosvenor Museum in Chester, I was keen to gain work experience in an archive. I was lucky to be given the opportunity to work at Keele University’s Special Collections and Archives. I want to thank Helen Burton for adapting my placement so I could continue to work despite the national lockdown, and for trusting me with the work.

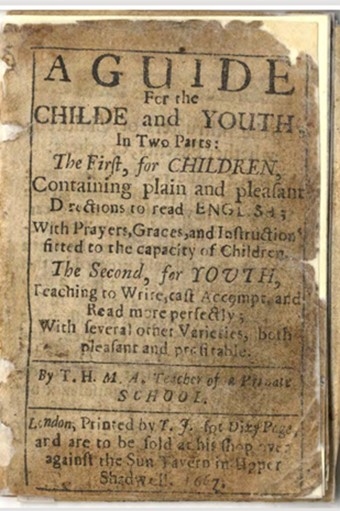

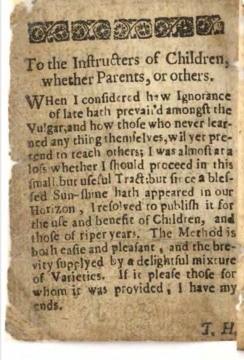

A Guide for the Childe and Youth

Title page

Title page

A guide for the childe and youth. In two parts: the first, for children, containing plain and

pleasant directions to read English; with prayers, graces, and instructions fitted to the

capacity of children. The second, for youth, teaching to write, cast accompt, and read

more perfectly; with several other varieties, both pleasant and profitable.

by T. H., M.A., Teacher of a private school

London, printed by T.J. for Dixy Page, and are to be sold at his shop over against the Sun

Tavern in Upper Shadwell, 1667.

I’ve been researching the history of this fascinating little book which found its way into the Archives as part of a collection of ephemera, passed to the University Library in the 1950s by Miss Eliza Tittensor, a retired local schoolteacher. Amazingly, it’s understood to be the only surviving copy of the edition printed in 1667. Nine later editions were published between 1711 and 1796 (see http://estc.bl.uk/) but the discovery of this earlier edition changes our previous understanding that this famous rhyming alphabet originated in The New England Primer of 1689. The volume has been digitised and is available online.

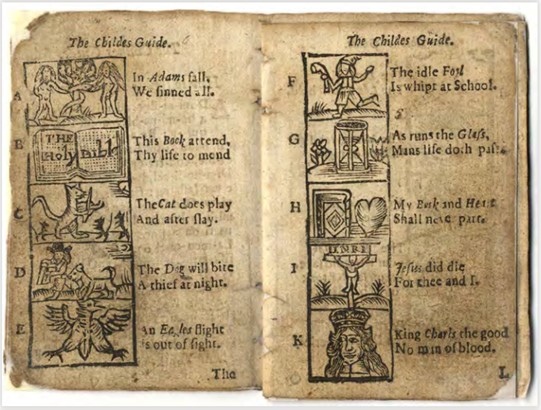

A Guide for the Childe and Youth (1667) Rhyming alphabet with woodcut illustrations

A Guide for the Childe and Youth (1667) Rhyming alphabet with woodcut illustrations

The Author

The identity of the author and publisher of the Guide is not provided, as both the author (T.H.) and the printer (T.J.) left their names abbreviated. At the time of the Guide’s publication, books were subject to controls and censorship, and until 1695 the Stationers’ Company restricted printing to the capital and the university cities of Oxford and Cambridge. It’s possible that the author and publisher wanted to remain anonymous to protect themselves from breaching any potential restrictions.1

A student from UCL researched the Guide a few years ago and looked in alumni directories to find the identity of the author. Jonny Leech found two potential candidates sharing the initials T.H: Thomas Haughton of Shropshire, who lived approximately 1637-1697, and Thomas Hawkesworth of the West Riding of Yorkshire, who lived approximately 1630-1728. Although I’ve investigated this further, I’ve been unable to find evidence to support which of these candidates might be the correct one.

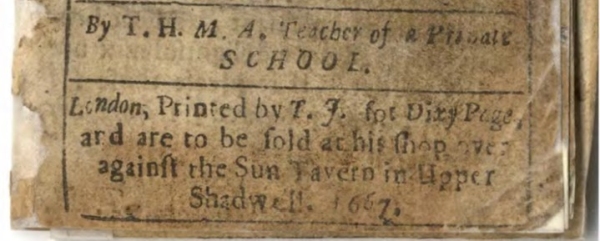

Enlarged section of the title page

Enlarged section of the title page

The Printer and the Bookseller

Further investigation of printers and booksellers working in England led me to information on the London seller of our book, Dixy Page. I discovered that in April 1666, a year prior to the publication of the Guide, Dixy Page and the printer Thomas Johnson were imprisoned for dispersing seditious books and were bound over in a sum of £500.2 As Thomas Johnson is linked to Dixy Page during this period, we can presume that Johnson is our anonymous printer T.J., solving this particular mystery.

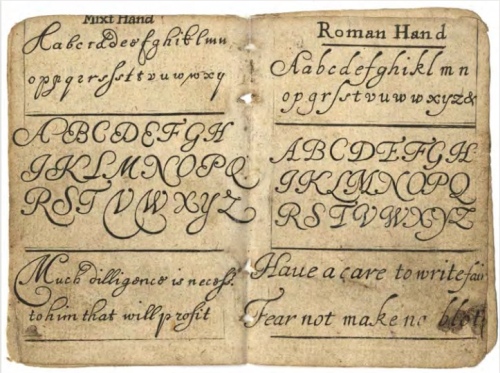

Book Construction

Interestingly, even though it’s difficult to tell from looking at scanned images, the Guide is just 8.7cm x 6.cm in size. The reduced size would have helped to keep costs down as book production was very labour intensive and expensive in the seventeenth century. Books created in this style are commonly referred to as ‘chapbooks’ and the small size is achieved by printing on a single sheet of paper, then repetitively folding in half until the correct size is reached. Our book is a sextodecimo, meaning each printed sheet has been folded into sixteen leaves (thirty-two pages).

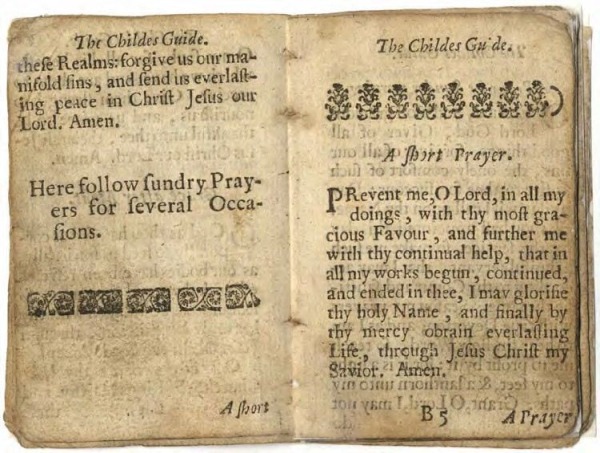

Pages inside the Guide demonstrating the use of a catchword. ‘A Short’ can be seen on the bottom of the left page, with a ‘A Short Prayer’ being the start of the next page.

Pages inside the Guide demonstrating the use of a catchword. ‘A Short’ can be seen on the bottom of the left page, with a ‘A Short Prayer’ being the start of the next page.

The printer would assemble the pages in the correct order by using ‘catchwords’ which show the first word of the page in the bottom corner of the previous page. The folded pages, known as gatherings, would then be hand-sewn together to create a small book.

Ownership Marks

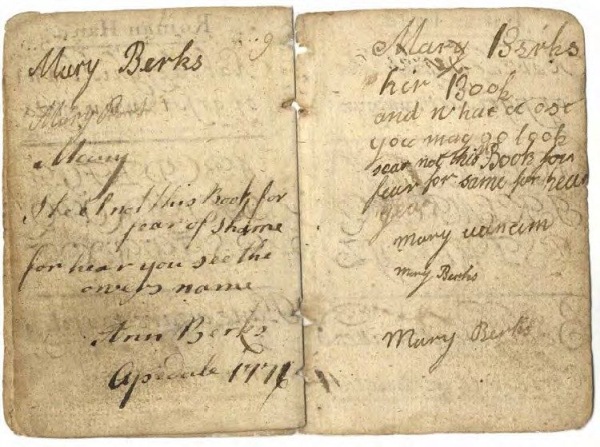

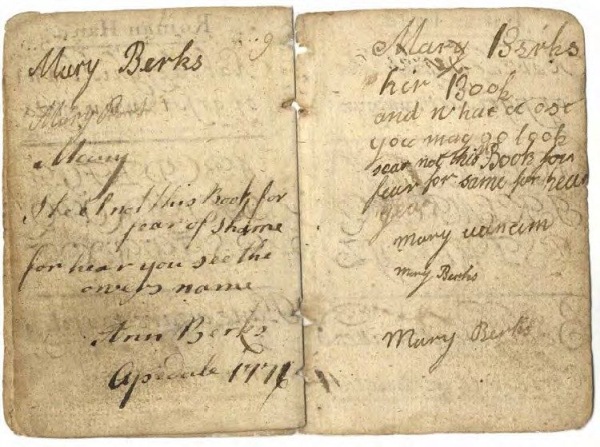

Handwriting by Mary and Ann Berks, dated 1776, found inside A Guide for the Childe and Youth

Handwriting by Mary and Ann Berks, dated 1776, found inside A Guide for the Childe and Youth

The book’s ownership history can be traced to North Staffordshire, as it contains handwriting from a Mary and Ann Berks living in Apedale in 1776. We can only speculate how Mary and Ann Berks came into possession of the Guide more than a century after it was published, but the fact that such a small book survived demonstrates how it was valued and well cared for. So who were Mary and Ann?

An Apedale Connection

I was keen to find out more about Apedale and the Berks family, and to discover what their life would have been like in North Staffordshire in the eighteenth century. An online search of Gateway to the Past leads to documents showing a Robert Berks of Apedale. Within these documents Robert is referred to as a ‘yeoman’, a term describing someone who worked their own land but not necessarily as a freeholder. Robert is present in the settlement of disputes over the amount of coal tenants could receive in the parishes of Madeley, Audley, Keele and Wolstanton in 1766.3 An intriguing find linking the Berks name to Apedale’s history of mining.

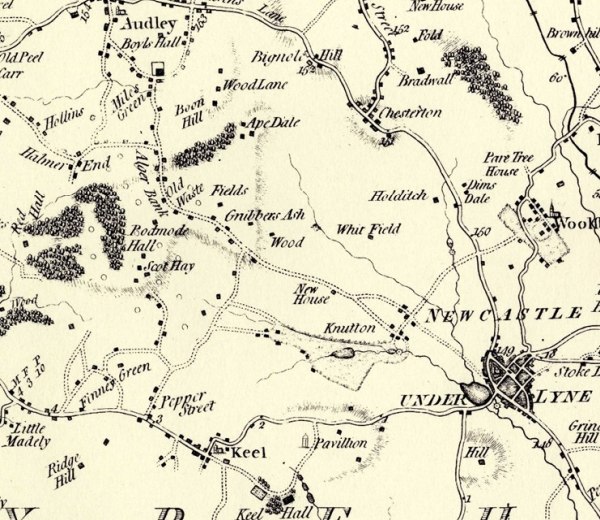

Map of Apedale from A Map of the County of Stafford by William Yates, 1775

Map of Apedale from A Map of the County of Stafford by William Yates, 1775

A year before Ann wrote in her book there was an important development for the mining industry in Apedale, as Parliament allowed for a canal to be built in 1775, and it was completed three years later in 1778. Apedale in the mid eighteenth century was already a busy landscape of small mines and furnaces, and with the growing demand for coal, the area was deemed worthy of investment. The development of the canal allowed for the transport of a regular supply of coal to Newcastle under Lyme, though it was never connected to the main canal system. Apedale was becoming more industrialised, and the archival evidence suggests that the Berks family were increasing their wealth and becoming part of an emerging, educated class.

A Sneyd Connection

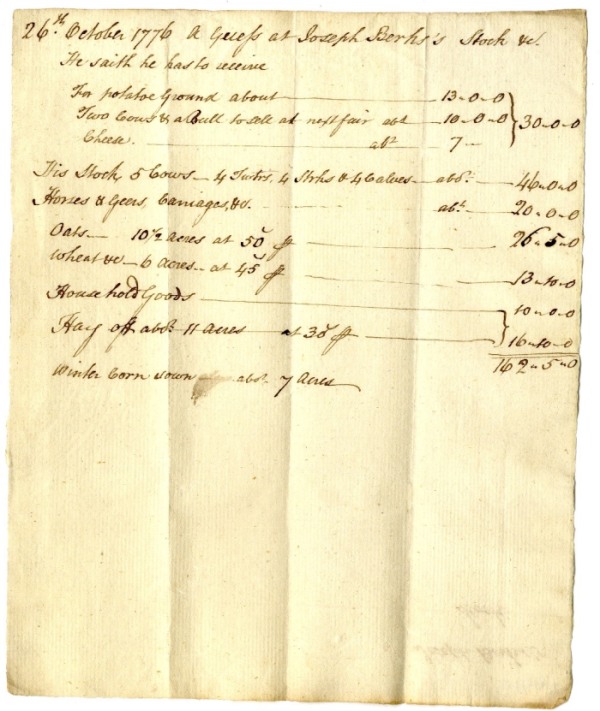

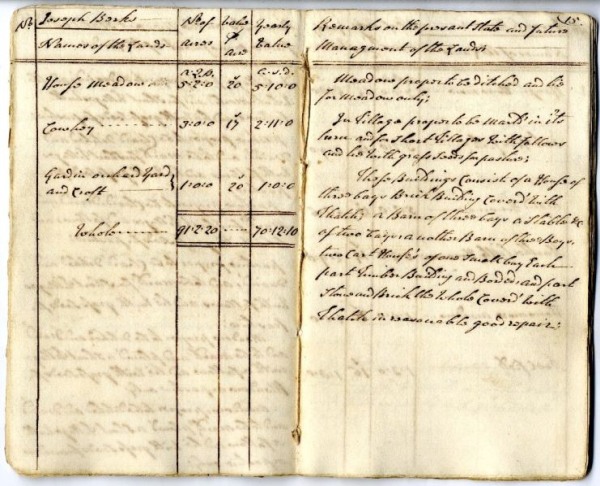

'A Guess at Joseph Berks’ stock', October 1776 (Sneyd Papers GB172 S1647 Keele University Library)

'A Guess at Joseph Berks’ stock', October 1776 (Sneyd Papers GB172 S1647 Keele University Library)

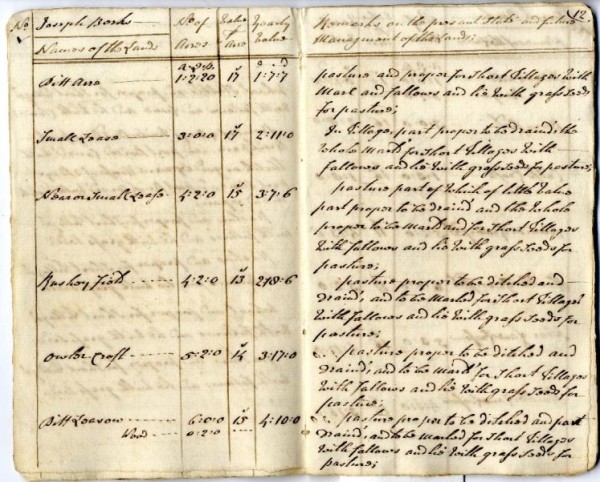

Given the mention of the Keele estate, I decided to search the catalogues to the Sneyd Papers in the University’s Special Collections and Archives. I discovered another Berks named Joseph, and a list of his agricultural stock from 1776, the same year Ann Berks made her mark in the Guide. Joseph’s stock list includes potatoes, cheese, horses, cows, oats, wheat and hay, and he can also be found in a 1772 survey, leasing pasture, meadow and farm buildings from Ralph Sneyd.

Sneyd Survey and Valuation, 1772 (Sneyd Papers GB172 S1634 Keele University Library)

Sneyd Survey and Valuation, 1772 (Sneyd Papers GB172 S1634 Keele University Library)

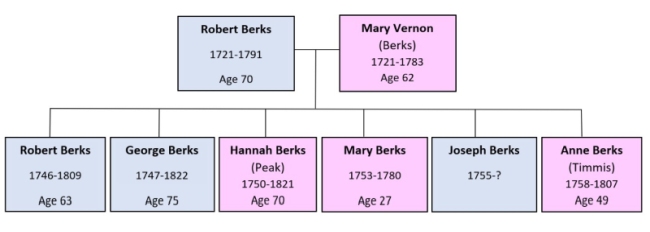

Finding the Berks family

Finding the Berks family was complicated by the variations in spelling in official records (Berks as Birks, and Ann as Anne). To locate a Berks family in Apedale with two girls of the correct names and ages, I began to search through Ancestry, encouraged by the fact that previously I’ve been successful in using the resource for my own family tree. After looking through the records I discovered a Robert Berks (1721-1791) buried at Apedale, and within his family tree found six children, including sons named Robert (most likely our mining disputes arbitrator), Joseph (who probably leased Sneyd’s land), and daughters Mary (1753-1780) and Anne Berks (1758-1807), surely the owners of our Guide.

Berks family tree

Berks family tree

Ann would have been seventeen or eighteen when she signed her name, suggesting that the author’s aim of providing an educational tool for both the ‘Childe’ and ‘Youth’ was achieved, as the Guide was still being used by young adults. Looking at the handwriting from Mary, it appears she had written inside the book at a younger age and left it undated. I wonder whether Ann and Mary rediscovered the Guide several years later and decided to claim ownership of the book, as well as demonstrate their much-improved hand, as they wrote:

“I keep not this book for fear of shame for hear [sic] you see the owners name”

“I keep not this book for fear of shame for hear [sic] you see the owners name”

Binding

The homemade calfskin leather binding (disbound for paper conservation)

The homemade calfskin leather binding (disbound for paper conservation)

Originally the Guide would have been sold with a paper cover as bindings were very expensive to produce. Bookbinding developed as a separate craft, with binders making bespoke coverings for customers. From the mid-eighteenth century more ready-bound editions were being produced and becoming more affordable.

The Guide is protected by a homemade calfskin leather binding which could be the early work of Mary or Ann Berks, though we might expect them to be more skilled at sewing. Nonetheless, it’s an interesting and unique example of an amateur practicing the craft of bookbinding to protect a treasured volume.

Children's Literacy

The author explains the purpose behind the book, airing concern that children are receiving a poor education from unqualified teachers. He writes:

“To the Instructors of Children, whether Parents, or others. When I considered how Ignorance of late hath prevail’d amongst the Vulgar, and how those who never learned any thing themselves, wil [sic] yet pretend to teach others; I was almost at a loss whether I should proceed in this small but useful Tract: but since a blessed Sunshine hath appeared in our Horizon, I resolved to publish it for the use and benefit of Children, and those of riper years. The method is both easie and pleasant, and the brevity supplyed by a delightful mixture of Varieties. If it please those for whom it was provided, I have my ends.”

We can assume the author achieved his goal as we’ve learned that the book remained in print for decades, influencing other works such as The New England Primer (see American Antiquarian Society). The teachings provide us with an insight into what it was like to be a child during the seventeenth century, and how teaching from the past has shaped education today. Content includes moral instruction, religious teachings, varied handwriting techniques, as well as Latin.

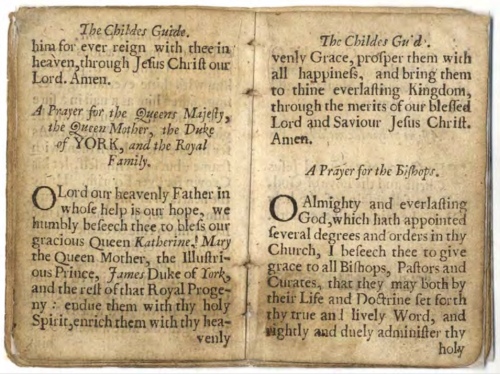

The Guide contains prayers for King Charles II, Queen Katherine, Mary the Queen Mother and James Duke of York, providing us with an understanding of how children were taught to love and respect the monarchy. Mary and Ann lived during the reign of George III, by which time the political and monarchical messages in this edition had become outdated. Nevertheless, the book was still in use, indicating it was still considered a valuable tool for learning and teaching.

I find it intriguing that there are no markings to provide evidence that our book was used by a boy, when Mary and Ann had three brothers. We know that less importance was placed on the education of females at this time, so it’s possible that the boys attended school and studied contemporaneous texts, whilst the girls were home-schooled and received a more basic education with the century old Guide.

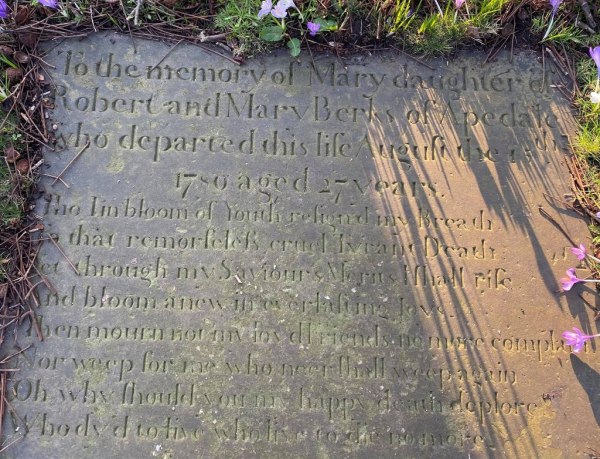

Visit to a churchyard

From the records shown on Ancestry, I located Mary Berk’s grave as being at St James the Great churchyard in Audley. As there are no photos to be found online, I decided to try and find the grave with the help of my partner. One of the issues we encountered was that most of the older grave stones lay flat and over time have either become covered in moss or have been badly worn down. After searching for an hour and almost completing a loop of the churchyard we were both convinced that Mary’s grave had become unrecognisable. Yet, as we were about to leave the churchyard we spotted it! It was quite emotional to realise that Mary, the girl who had written inside our book, had died soon after at the young age of 27. Nonetheless it was comforting to see that the grave remains in good condition, surrounded by beautiful flowers.

Mary Berks grave at St James the Great’s Churchyard in Audley.

‘To the memory of Mary daughter of

Robert and Mary Berks of Apedale

who departed this life August the 15th

1780 aged 27 years.

Tho I’m bloom of Youth resigned my Breath

To that remorseless cruel Tyrant Death

Yet through my Saviour’s Merits I shall rife

And bloom a new in everlasting love

Then mourn not my lov’d Friends no more complain

Nor weep for me who ne’er shall weep again

Oh why should you my happy death deplore

Who dy’d to live who live to die no more’

Footnotes

1 A. Murphy, ‘The history of the book in Britain, c.1475–1800’, in Suarez, M.F. & Woudhuysen, H. R. (eds.), The Oxford companion to the book, Oxford 2010, ch.20a.2.

2 Henry Robert Plomer, ‘A dictionary of the booksellers and printers who were at work in England, Scotland and Ireland from 1641 to 1667’ (London: Blades, East & Blades, 1907) p.143.

3 Articles of agreement to settle disputes about the amount of coal each tenant may get, in several mines, veins or rowes of coal in the parishes of Madeley, Audley, Keele and Wolstanton, (1766) Gateway to the Past D463/M/B/1, Staffordshire Record Office.

Further Reading

Avery, G., Origins and English predecessors of the New England Primer, Proceedings of the American Antiquarian Society (April 1998, vol 108, part 1, pp.33-61).

Eliot, S., and Rose, J., eds., A Companion to the History of the Book (Oxford 2007).

Pearson, D., Books as History: The Importance of Books Beyond Their Texts (British Library, 2008).

Raven, J., The Business of Books: Booksellers and the English Book Trade 1450-1850 (Yale University Press, 2007).