Sam Elphick

Fear, blue jeans and plaid shirts; or, why environmentalists took so long to stop worry and love nuclear power

In March 2011, the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant suffered three meltdowns, three hydrogen explosions, and three radioactive releases after the Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami. Fukushima prompted international shock, and I’m sure many readers will remember their own shock when they turned on the news early in the morning to see the coverage. It was eventually classified as being a disaster on the same scale as the 1986 Chernobyl disaster.[1]

Yet in 2019, a poll conducted in the United States showed that as many as 45% of Americans were for the use of nuclear power in climate policy – in opposition were 37%, with 18% deeming nuclear power ‘essential’ in the fight to stop climate change: Fukushima has not had a significant impact on the public opinion of nuclear power.[2] To certain environmentalists, the effects of nuclear disasters such as Fukushima are acceptable. British activist George Monbiot went so far as to say that “…the impact on people and the planet has been small. The crisis at Fukushima has converted me to the cause of nuclear power.”[3]

But, the surging interest in pro-nuclear environmentalism should not be considered a ‘birth’ of a new school of thought, but rather a ‘re-kindling’ of previously stunted arguments for the environmental positives of nuclear power. As I shall demonstrate, these anchors to growth go back to the 1970s, and two primary groups. First is a group of ‘blue jeans and plaid shirts’: Nuclear Scientists who frequently produced arguments that showcased the ‘glory’ and endless benefits of their field – and secondarily producing perhaps the greatest conflict of interest in environmentalism ever. The second group includes early environmental scientists who struggled to conceive of nuclear weapons and nuclear energy as separate environmental issues and fought against ideas of pro-nuclear scientists such as James Lovelock - inventor of the first device used to detect CFCs in the atmosphere, and of the GAIA hypothesis. It is in the way that these two groups developed their ideas that has stunted the growth of pro-nuclear environmentalism and prevented an actual serious movement from ever forming, despite any occasions of majority public support.

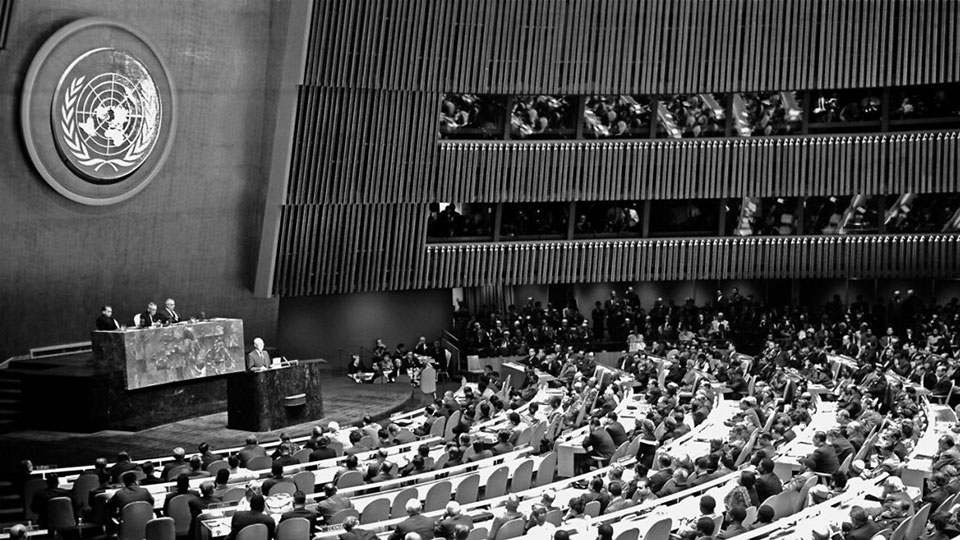

Figure 1. U.S. Pres. Dwight D. Eisenhower delivering his Atoms for Peace speech to the United Nations, Dec. 8, 1953.[4]

One the 8th December, 1953, President Dwight D. Eisenhower gave a speech to the UN General Assembly. In it, Eisenhower delivered these lines: “I therefore make the following proposal. The governments principally involved… should begin now and continue to make joint contributions from their stockpiles of normal uranium and fissionable materials to an international atomic energy agency… The more important responsibility of this atomic energy agency would be to devise methods whereby this fissionable material would be allocated to serve the peaceful pursuits of mankind.”[5] This speech is popularly remembered as the ‘Atoms for Peace’ speech. Following the speech was the creation of the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) in July 1957; and a re-focusing of the U.S.A.s Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) towards nuclear power, with an experimental nuclear power plant beginning construction in 1954.[6] From this speech to around the 1960s, American nuclear energy (under the AEC headed by David Lilienthal) enjoyed generous federal funding, particularly as it was seen as the best -and most rapid - method to ‘ease the sense of national guilt’ over Hiroshima and promote nuclear technology as a peaceful development.[7] However, the nuclear industry was criticised frequently for being un-economic and producing the environmental hazard of nuclear waste.[8] By the early 1970s these had become the main criticisms of nuclear energy (especially during the 1973 Oil Crisis), and with very little positives, the nuclear energy industry found itself as ‘a solution in search of a problem’.[9]

This problem appeared in the late 1970s-early 1980s. The increasing scientific acceptance that CO2 emissions were causing a global warming provided an excellent jumping-off points for nuclear energy scientists worried about the survival of their field. Thus, the first environmental nuclear scientists began furiously presenting arguments that took the existing knowledge of nuclear power’s lack of air pollution and demonstrated nuclear energy’s ‘wonderous solutions’ to the end of the world. However, these scientists were often removed from public discourse: they’d almost exclusively attend ‘formal sessions over dining tables, wearing blue jeans and plaid shirts, and carrying graphs and slides for their points’.[10] These private and complicated discussions prevented the ‘blue jeans and plaid shirts’ group from having connection to the public about the environmental positives of nuclear energy. On top of this, the scientists did no favours for themselves in the earning of public trust, especially when considering the ways in which previous nuclear effects were demonstrated. In 1956 a calculation was made assessing the effects of nuclear testing: ‘testing produced 2 additional birth defects per every 1,000 live births. In a population of 150 million, that amounted to 300,000 birth defects in one generation.’[11] However, the calculation was presented by nuclear scientists as this: ‘background radiation from natural sources, such as cosmic rays, produce 20 birth defects per every 1,000 live births. Nuclear testing brings this up to 22 per 1,000.’[12] While both are true, the second statement seen by the public is clearly dishonest, and as such through repeated statements such as these the late 20th century public learnt to distrust nuclear scientists; something not helped by the obvious conflict of interest of the scientists using global warming as a crutch to provide a future for their field. Furthermore, despite using environmentalist terms to create support for nuclear energy, nuclear scientists continued to blame and vilify environmentalist critics. Alvin Weinberg – a member of the Manhattan project – said at the 1989 conference on nuclear energy that ‘nuclear power will not return, unless the sceptical elite of environmentalists persuaded the public.’[13] Clearly, late-twentieth century nuclear scientists stunted the growth of pro-nuclear environmentalism through vilification of environmentalists and repeated betrayals of public trust.

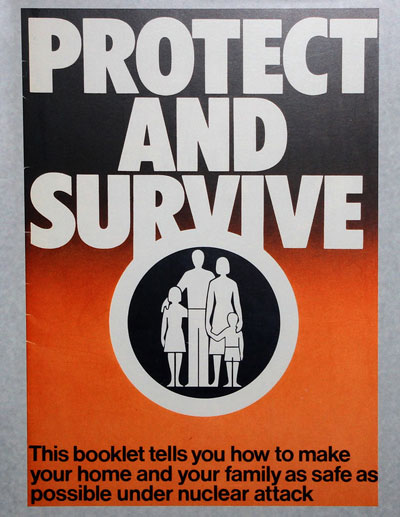

The other group to have stunted the growth of a pro-nuclear environmentalism were the early environmentalists. Immediately following the Hiroshima bombing, there emerged a split in the British public opinion of the atomic technology. Most viewed it as a destructive force used by the anarchy of superpower competition. Others viewed it in a more optimistic light (too optimistic from today’s point of view), with atomic energy promising free electricity and atomic cars, to the ability to alter Britain’s climate.[14] Most environmentalists seemingly missed the optimistic boat. Former Greenpeace member Patrick Moore was firmly against nuclear energy up until 2000 – when he apparently had an epiphany after talking to James Lovelock (who apparently had always aligned more with the second option expressed by the British public).[15] According to Moore, Environmentalists had behaved emotionally rather than logically towards nuclear power during the 1950s-1980s.[16] In fairness, this is a rather understandable reaction to nuclear technology. The 1961 Berlin and 1962 Cuban Crises terrified millions, shattering previously built ideas of a peaceful atom. Furthermore, civil defence drills, shelter campaigns, and famous school films such as Bert the Turtle heightened public anxiety.[17] Thus it is understandable that Environmentalists thought that there was going to be a certain post-nuclear future: one where either there had been a nuclear holocaust or one where nuclear technology had been declared dead and buried. This drive was immensely important in inspiring dis-armament campaigns, but it is the same emotional drive that caused Environmentalists to overlook the green benefits of nuclear power, thus stunting the growth of a pro-nuclear environmentalist movement. In modern times, following a lack of ‘hot nuclear crises’ and a lack of anxiety-inducing government campaigns, pro-nuclear environmentalism has grown, thus demonstrating further the obstruction that late 20th century fear caused.

Figure 2: Protect and Survive (1980).[18]

The two groups of the ‘blue jeans and plaid shirts’ scientists and the ‘emotional’ Environmentalists stunted the serious growth of pro-nuclear environmentalism until the 21st century. However, now-a-days the majority of scientists have firmly committed to combating climate change, and an ever-increasing number of Environmentalists are decoupling nuclear energy from nuclear weapons. Plus, current technology has committed to a process of ‘recycling’ atomic fuel for nuclear energy, therefore lessening the primary environmental worries about nuclear waste.[19] Unless there is either another ‘hot’ diplomatic crisis between nuclear powers in the 21st century, or a sudden increase in dishonest scientific nuclear statements, popular support for pro-nuclear environmentalism is likely to continue to rise in the present given the ongoing reassessments of nuclear power’s role in combating climate change.[20] Current UK Government policy has been especially committed to a re-funding of the atomic energy sector in the name of ‘net-zero energy’, demonstrating that perhaps now in a time where everybody is ‘green’, nuclear energy has suddenly become very attractive as a power system.[21]

[1] ‘Japan: Nuclear crisis raised to Chernobyl level’, in BBC, (12/04/2011), https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-asia-pacific-13045341, accessed 08/12/2021

[2] National Green Advocacy Project Polling, Green Advocacy Project, (March 5-6, 2019, Change Research, USA), https://docs.google.com/presentation/d/1EZVcFhUBfZU6i6VoGJYwH9BRJ6bSSjCL2v6B8-pR8Sw/edit#slide=id.g568bd88eea_0_0, accessed 23/11/2021

[3] Monbiot G., Going Critical, (21/03/2011), https://www.monbiot.com/2011/03/21/going-critical/, accessed 23/11/2021

[4] Nuclear Regulatory Committee, 'President Eisenhower delivers Atoms for Peace Proposal', (1953), Available at: Preisdent Eisenhower delivers Atoms for Peace proposal | Flickr. Public Domain: About Nuclear Regulatory Commission | Flickr

[5] Eisenhower D. D., ‘Atoms for Peace’, found in World Nuclear University, https://web.archive.org/web/20110330222020/ http://www.world-nuclear-university.org/about.aspx?id=8674&terms=atoms%20for%20peace, accessed 08/12/2021

[6] Lowen R. S., ‘Entering the Atomic Power Race: Science, Industry, and Government’, in Political Science Quarterly, Vol.102, Issue 3, (1987), p.459

[7] Ibid. p.460, and Boyer P., ‘Sixty years and counting: nuclear themes in American culture, 1945 to the present’, in Grant M., Ziemann B., (eds.), Understanding the Imaginary War: Culture, Thought and Nuclear Conflict, 1945-90, (Manchester University Press, Manchester, 2016), p.76

[8] Manning R.,’ The Future of Nuclear Power’, in Environment, Vol. 27, Issue 5, (May 1985), p.17, and Palfrey J. G., ‘Energy and the Environment: The Special Case of Nuclear Power’, in Columbia Law Review, Vol.74, Issue 8, (Dec. 1974), pp.1375-1409

[9] Uekoetter F., ‘Fukushima, Europe, and the Authoritarian Nature of Nuclear Technology’, in Environmental History, Vol.17, Issue 2, (2012), p.280 [Uekoetter was talking about the 2000s here, but I thought their point could be transferred smoothly to the late 1960s]

[10] Wald M. L., ‘Renewed Debate on Nuclear Power’, in The New York Times, (23/10/1989), in https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/A175767206/STND?u=keele_tr&sid=bookmark-STND&xid=91c6fc1f, accessed 07/12/2021

[11] Hamblin J. D., ‘Fukushima and the Motifs of Nuclear History’, in Environmental History, Vol.17, Issue 2, (2012), pp.288-289

[12] Hamblin J. D., ‘Fukushima and the Motifs of Nuclear History’, in Environmental History, Vol.17, Issue 2, (2012), pp.288-289

[13] Wald M. L., ‘Renewed Debate on Nuclear Power’, in The New York Times, (23/10/1989), in https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/A175767206/STND?u=keele_tr&sid=bookmark-STND&xid=91c6fc1f, accessed 07/12/2021

[14] Grant M., ‘The imaginative landscape of nuclear war in Britain, 1945-65’, in Grant M., Ziemann B., (eds.), Understanding the Imaginary War: Culture, Thought and Nuclear Conflict, 1945-90, (Manchester University Press, Manchester, 2016), p.96

[15] Gelinas N., ‘The environmentalist who went nuclear: why Greenpeace founder and activist Patrick Moore thinks the atom is the answer’, in Chief Executive, Issue 228, (Sept. 2007), p.46

[16] Moore P., ‘The Environmental Movement: Greens have lost their way’, in The Miami Herald, (13/05/2012), at http://greenspiritstrategies.com/the-environmental-movement-greens-have-lost-their-way/, accessed 08/12/2021

[17] Boyer P., ‘Sixty years and counting: nuclear themes in American culture, 1945 to the present’, in Grant M., Ziemann B., (eds.), Understanding the Imaginary War: Culture, Thought and Nuclear Conflict, 1945-90, (Manchester University Press, Manchester, 2016), pp.78-79

[18] Leo Reynolds, 'Protect and Survive', (2013). Available at PROTECT AND SURVIVE | Royal Air Force Museum Cosford Shifnal… | Flickr. Distributed under a CC license: Creative Commons — Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 2.0 Generic — CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

[19] Feiveson H., Mian Z., Ramana M. V., Von Hippel F., ‘Managing nuclear spent fuel: policy lessons from a 10-country study’, in Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, (27/05/2021), at https://thebulletin.org/2011/06/managing-nuclear-spent-fuel-policy-lessons-from-a-10-country-study/, accessed 08/12/2021

[20] Birmingham Policy Commission, The Future of Nuclear Energy in the UK, (University of Birmingham, Birmingham, 2012), at https://www.birmingham.ac.uk/documents/research/socialsciences/nuclearenergyfullreport.pdf, accessed 08/12/2021

[21] Kwarteng K., ‘UK backs new small nuclear technology with £210 million’, from Department for Business, Energy, & Industrial Strategy, UK Government, (09/11/2021), at https://www.gov.uk/government/news/uk-backs-new-small-nuclear-technology-with-210-million, accessed 08/12/2021, and Haves E., ‘Nuclear power in the UK’, In Focus, UK Parliament, (House of Lords Library, 01/12/2021), at https://lordslibrary.parliament.uk/nuclear-power-in-the-uk/, accessed 08/12/2021, and Hands G., ‘Speech given at Nuclear Industry Association annual conference 2021’, Department for Business, Energy, & Industrial Strategy, UK Government, (02/12/2021), at https://www.gov.uk/government/speeches/nuclear-industry-association-annual-conference-2021, accessed 08/12/2021