Wartime at Keele, War Service and National Service

In 1939 the Keele Park house estate was requisitioned by the military for wartime use. The Hall was occupied and dozens of temporary buildings were erected to house troops - many of whom were in transit. Forces evacuated from Dunkirk in 1940 certainly passed through Keele and the camp was used for training of various kinds.

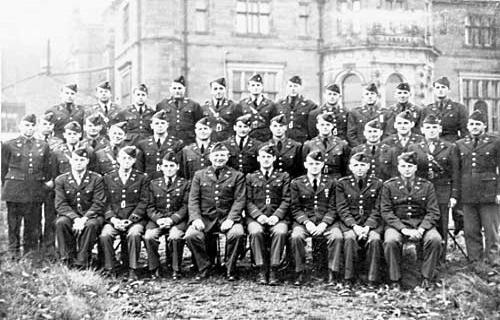

American forces, including the headquarters of the US 83rd Division, were stationed at Keele Hall IN 1944. The American barracks huts were far superior to their earlier British counterparts and remained in active use on campus for four decades.

American forces, including the headquarters of the US 83rd Division, were stationed at Keele Hall IN 1944. The American barracks huts were far superior to their earlier British counterparts and remained in active use on campus for four decades.

After the war the base was converted into a camp for refugees and was also occupied for a time by Polish soldiers in transit back to Poland. Italian and German prisoners of war lived and worked locally, on farms and at the Madeley Tile Works.

The photo (above right) is the only known image of American troops at Keele. It shows Officers on the lawn at Keele Hall. (Photo: courtesy of Brampton Museum, Newcastle-under-Lyme Borough Council). The lack of an Army insignia suggests these officers were part of US Third Army which was kept "incognito" until after the invasion of Normandy - the 83rd Division was assigned to the Third Army. On the back it is identified as "Colonel Stark and staff". Another record indicates that: "From 1-16 June 1944 the 83rd Division band was at Keele Hall, Stoke-on-Trent".

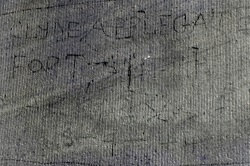

"Standing by Keele Hall gates with Alan Ewart (Security Officer) in 2012, I was shown, to my astonishment, a faint inscription he had spotted in the stone high up on the inner side of the column supporting Fresher's Gate. I'd never noticed it before.... There, almost illegible now, is a scratched message dating apparently from the American base on the Keele Hall estate during the Second World War." John Easom (1981)

The photo (left) of the inscription isn't too clear but it reads:

The photo (left) of the inscription isn't too clear but it reads:

Clyde Applegate

Fort Smith

Arkansas

5-9-44

Was he an American serviceman stationed at Keele in 1944? The date is 9 May 1944, less than a month before D-Day.

The Command Post of the US 83rd Infantry Division was stationed at Keele Hall from 19th April to 14th June 1944. The troops were trained at locations across Wales and Shropshire. The command post then proceeded to a base near Stonehenge before landing in Normandy on 25th June, before seeing heavy fighting until the end of the war.

Peter Davis (1963) discovered the following: Quinton Clyde Applegate, age 27 died in a Little Rock Hospital November 8, 1948 after a long illness. Surviving are his wife, Mrs Pauline Applegate, of Fort Smith; his mother Mrs Lue Suggs, near Belleville; Mrs Ina smith, of Hackett; two brothers, Clon, of Merced, Calif., Hison, of St. Paul, Nebraska. Also a host of other relatives and friends. He was laid to rest in the National Cemetery at Fort Smith, Friday, November 12 1948 from the Yell County Record, Danville, Arkansas, Thursday, November 18, 1948)

Dr David Hampson (1963) lives in Cincinnati, Ohio, and he was also hot on the trail; he discovered the following and even made contact with the family: The Fort Smith (Arkansas) Genealogical Department has confirmed his full name was Quinton Clyde Applegate. He was among the troops stationed on the Keele Hall estate during the Second World War. The name Quinton was an embarrassment for a young man in the US Army. So, he went by the name of Clyde. After the war, he returned to Fort Smith and died after a two-year illness. He is buried in the National Cemetery. He was married but had no children. His widow married Clyde's young brother - they had a daughter Katherine. Katherine is still living in the Fort Smith area. David contacted Katherine: "She was fascinated to hear about her uncle's inscription at Keele." Well done, Messrs Davis and Hampson - or should that be Dr John Hampson and Mr Sherlock Davis?

History student Tom Williams (2020) researched the finding of a Second World War-era NAAFI cup (photo right). The cup was discovered by workers digging trenches for new pipework along Central Drive. During the war, the Navy, Army and Air Force Institutes (NAAFI) provided canteens, shops and other facilities for the British Armed Forces on military bases across the country, including the camp at Keele. NAAFI crockery was mass-produced during wartime and this cup was possibly manufactured by local company ‘Wood & Sons’ of Burslem. He said, "It is amazing to see reminders of our unique history still being discovered around campus to this day, who knows what else could be hidden!"

History student Tom Williams (2020) researched the finding of a Second World War-era NAAFI cup (photo right). The cup was discovered by workers digging trenches for new pipework along Central Drive. During the war, the Navy, Army and Air Force Institutes (NAAFI) provided canteens, shops and other facilities for the British Armed Forces on military bases across the country, including the camp at Keele. NAAFI crockery was mass-produced during wartime and this cup was possibly manufactured by local company ‘Wood & Sons’ of Burslem. He said, "It is amazing to see reminders of our unique history still being discovered around campus to this day, who knows what else could be hidden!"

National Service was formalised as a peacetime form of conscription by the National Service Act 1948. From 1st January 1949, healthy males aged 17 to 21 years were expected to serve in the Armed Forces for 18 months and to remain on the reserve list for four years. Men were exempt from National Service if they worked in one of the three "essential services" of coal-mining, farming and the Merchant Navy. Exemption was also possible for conscientious objectors. In October 1950 the service period was extended to two years but the reserve period was reduced by six months. National Servicemen who showed promise could be commissioned as officers. National Servicemen served in combat operations in Malaya, Cyprus, Kenya, Korea, and elsewhere. National Service ended on 31st December 1960, but those who had deferred service for reasons such as university studies or on compassionate or hardship grounds still had to complete their National Service after this date.

National Service was formalised as a peacetime form of conscription by the National Service Act 1948. From 1st January 1949, healthy males aged 17 to 21 years were expected to serve in the Armed Forces for 18 months and to remain on the reserve list for four years. Men were exempt from National Service if they worked in one of the three "essential services" of coal-mining, farming and the Merchant Navy. Exemption was also possible for conscientious objectors. In October 1950 the service period was extended to two years but the reserve period was reduced by six months. National Servicemen who showed promise could be commissioned as officers. National Servicemen served in combat operations in Malaya, Cyprus, Kenya, Korea, and elsewhere. National Service ended on 31st December 1960, but those who had deferred service for reasons such as university studies or on compassionate or hardship grounds still had to complete their National Service after this date.

Photo: The residents of "Ahrschede" Hut in 1952 - an accented spelling of "Our Shed"

Memories of National Service and War Service

"I count National Service as a life-giving educational experience on a par with school and university. While I endured National Service, I loathed pretty well every minute of it. But I soon came to realise that it was one of the best things that could have happened. I came from a grammar school and parsonage background. Leaving school on Friday and becoming a soldier on Monday was absolutely mind-bending. So 18 months later and still a soldier (just), I was being interviewed by Lord Lindsay. I longed to get back to studying, so any maturity that I brought with me to the campus was balanced, perhaps outweighed, by revelling in the opportunity to resume an academic way of life. So maybe Keele provided me with a longed-for extension of adolescence rather than me intruding a worldly-wise maturity into a youthful student body. In short, I hated the Army, I loved Keele: and I would have been infinitely the poorer if I had had to do without either of these life-enhancing experiences."

Martin Tunnicliffe (1956)

"My father, John Moulton (1954) (3/6/1914 - 25/3/1972) was in the original cohort of founding fathers of 1950. He must have appeared ancient as a 36 year old amongst all the youngsters. He was a councillor in Stoke in the 1940s, and on the Education Committee which decided to set up the University. He was born in Fenton and left school at 14, taking up an apprenticeship locally. He served his time and then was released at age 21 in 1935 due to the Depression. He joined the RAF and found himself as an aero-engine fitter in Hong Kong. After Hong Kong was overrun at Christmas 1941 he spent the next three and a half years as a POW at Kai Tak. He was liberated following the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombs and subsequent Japanese surrender. Because of their condition the ex-POW's were sent home the long way round - by boat over the Pacific and Atlantic and train across Canada - to fatten them up so they would not present such a horrific sight to the great British public. He married in January 1946 He married in January 1946 and I arrived in January 1947. He became a Bevin Boy (voluntarily), working in the Deep Pit at Hanley. Tiring of this and there being a less urgent need for coal he looked for things to do and to better himself. What made him want to study again, having left school at 14, I do not know, but UCNS gave him the opportunity at age 36. He graduated in 1954 with a Third in Sociology and History and spent the remainder of his life in Social Work. It was at this time that the University College of North Staffordshire was coming into being at Keele and the rest, as they say, is History."

John Moulton (1969)

"Keele Hall became the home of my late father-in-law John Chidlow ("Jack") when he volunteered for Military Service with the British Army in 1939. John Chidlow was born in Bradely, a small woody suburb near the now restored Pottery Kilns in Longport, on the road to Newcastle from Tunstall and Burslem. He enlisted for Army service in about 1939 as a married man with a daughter on the way. When I indicated to the Chidlow family that I was going to the University College of North Staffordshire in 1957 Jack entertained us with a tale I will always remember. Yes, he truly wanted to be involved in the fight for his country, but he fancied doing it his way. He came across some information that said the Military was looking for people who rode motorcycles to join the "elite' group known as the Military Police. In reality, he had never ridden a motorbike in his life, but he enrolled and was posted to Keele for training shortly thereafter. The first test he was given was to demonstrate his skills along with numerous other MP recruits that he could ride a motorbike. He had observed others kick-starting the bikes and sitting on the saddle twisting the accelerator and "whoosh" they were off. His turn came and he jumped astride the beast and took off down the paddocks of Keele, and was given a clean bill of health to become an MP, which of course involved further training - I hope to improve his competence as a rider as well as learning the role on the often unenvied task of being an MP. Once trained the MP's were put out into service in the UK, often to mop up the drunken troops who were living it up in the dens of places like Liverpool. I hardly dare draw on the anecdotes of his experiences in these clean-up operations, but I do not think he would mind if I mentioned that that was when he learned to drink. There was many a landlord who was grateful that the MP's had come to clean out the rowdies, and their recompense was to ask the guys to sit down and have a beer or two. Jack's MP days saw him join the North African campaign, and with the outing of Rommel's forces the residual British forces, MP's and all were moved over to the shores of Italy. I lose track of the years, but at least Jack ended up in Rome and stayed there to several months after the War was declared an end. As I recall from his descriptions he returned to Britain's shores 'demobbed' in 1946."

Alan Jones (1961)

You can read more about Jack's contribution to stonemasonry at Keele in Early pranks.

"I did the army and Keele sequence back to front. I was so attracted by the opportunity to enter the new university college at Keele that I asked for deferral of my army service on receiving from Keele acceptance of my application, a decision that, in retrospect, might not have served me optimally. The national service experience began in oft-mentioned style. All I recall of my first 24 hours therein was the unprecedented haircut and, at 0530h, the bawling voice and charging boots accompanied by the bellowed words "Get your feet on the DECK!" It was the first time I had wanted my Mum since I was in hospital for 5 months at the age of 6! I soothed myself with the thought that it would all be over in six weeks' time. In fact, this was optimistic. Horwood Hut 31 residentsFor reasons never explained, it soon emerged that the group in which I found myself was to undertake a further 4 weeks' commando training, also in Lichfield. So it was to be 10 weeks with no leave allowed in Wellington Barracks. Yet, apart perhaps from the first few days, I never did get around to hating national service. Perhaps this was helped along by the fact that the first crack in the army's apparently seamless rules and traditions came when, in my 7th or 8th week, I was allowed to be out of the barracks for 12 hours in order to attend the end of year Students' Union Ball at Keele (in full army uniform, of course). This was a chance to see Maryon Lloyd (1955), whom I later married. Afterwards I managed to get back into my barracks' bed at about 3am the following morning largely because of a slice of luck in the form of the driver of a car who gave me a lift for most of the way on the empty roads of the witching hours. It got better, too.

After the 10 hard weeks, I was posted to Beaconsfield, the location of the army's Educational Corps, for another 4 weeks of training. This was quite remarkably different, however, with emphasis on what it takes to teach full-time army chaps (squaddies) of varying intelligence and interest. A sergeant's three stripes came along with this and, thus trained and striped, I was offered a posting to NATO's (or what became NATO's) military headquarters at Fontainebleau, handily placed for Paris. It took me every bit of 15 seconds to accept. After 18 months in the Paris basin, I was offered a scholarship at McGill University in Canada, enabling me to research in deepest Labrador and write a Master's thesis. Again, the army was understanding and let me out a couple of months early so that I should not be late for my inauguration at McGill. Thus it was that I happened, narrowly, to avoid service during the Suez crisis. Thus, I can say in all honesty that I enjoyed my short time in the army for two reasons. First, because of my very good fortune in both training and postings and, second, because it was the army that made sure that I grew up at last. So, on both counts, I can be nothing less than grateful - and yet, Keele would surely have been an even richer experience, had I only had the foresight to tackle the national service duties first. Martin may well have got it right."

Edward Derbyshire (1954)

Photo above: Ed Derbyshire with Horwood Hut 31 in 1950

"Before John Hodgkinson became the University's first Registrar he had served during the Second World War in the army. Part of the time he had served in the secret British Resistance Organisation. I belong to a group researching the BRO, also known as Auxiliary Units."

Bill Ashby

"I gained a great deal of confidence during National Service, having been deferred. I was five years older than most National Service recruits in 1958. I didn't loathe my two years in the RAEC but benefited by teaching Junior Leaders, many of whom were from broken homes or it had been suggested by the magistrate that the army was preferable to borstal."

Anon

"As to my own military service ( I was called up before the passing of the National Service Act ) I look back on it with generally good memories. It did not contain the evils that one reads of in other tales of National Servicemen. I never experienced sadistic NCO's and my fellow soldiers were no different from the lads I grew up with in a Durham mining village. The battalion was sent where and when it was needed, so we got plenty of changes of scene and activity. I came up to Keele after service in Palestine, Cyprus, British Somaliland, Mogadishu and Kenya with a Light Infantry battalion.I cannot remember an hour of boredom and, in general, we were proud of what we were doing. All very non-PC in today's world but I have no regrets whatsoever about any of it. Jack Thomson was a WEA sponsored student with whom I shared a room, a name (almost) and a Geordie accent for two years in The Hawthorns. Jack Thomson served in the Western Desert during the war. However, he walked out of Finals (he was given Agrotat) and, so far as I am aware, never returned to Keele. Is it possible that he was allowed to re-sit Finals later? Remembering his Bolshie attitude (he was slightly left of Lenin) I would have thought it unlikely that he would have joined the Keele Society. Memories, memories."

Don Thompson (1955)

"I am trying to remember whether any other of the first lot of students had been in the forces during the 1939-45 war, as distinct from 'just' doing National Service. I remember that Bob Elmore had been in the Medical Corps, and he was a good bit older than the rest of us (10 years maybe) so maybe he had seen active service? John Harvey, who was one of the first lecturers of English and became Professor of English at Queen's, Belfast, had served in the Navy."

Anna Swiatecka (1954)

"John Harvey was a somewhat rotund gentleman. The story circulated that after his initial interview to lecture at Keele Lord Lindsay commented that he seemed somewhat large to have served in submarines. He was told that his main duty was to run to the appropriate end of the vessel for assistance in diving or surfacing. Whether this was believed or not was never made clear. More seriously and tragically, he died at a young age not long after taking up his post at Queen's, Belfast."

Bill Lighton (1954)

"TG" Miller was one of my Geology tutors. He was an incredible guy and campus mythology held that he had done some amazing James Bond-type work in occupied Norway during the war (I think that was how he met his wife, who I believe was Norwegian). My favourite memory of him was in class one day when Prof Cope marched in and interrupted what TG was saying with "Ah, Miller". TG turned and looked at him and said "Yes, Cope?", whereupon the Prof scuttled out."

Tony Budd (1963)

The cover of his book "Geology and Scenery in Britain" (Batsford, 1953) reveals that Terence G Miller served in Norway, Holland and Germany; latterly as a glider pilot with the 1st Airborne and 6th Airborne Divisions.

"Terence G "TG" Miller (1918-2015) was a lecturer/senior lecturer in the Department of Geology at from 1954 to 1965 Keele. During that period he inspired many students in his subject. Indeed when the plate tectonic revolution struck in the late 1960s those of us taught by him were already 'on message' because of his insight into the significance of recent geophysical and stratigraphic discoveries. The world of geography was shaken when in 1965 he was appointed to the Chair of Geography in the University of Reading. However, within two years he was on his way to become Principal of the University College of Rhodesia until 1970 when the Smith regime forced his resignation. Literally jumping out of the frying pan into the fire he soon became the Director of the North London Polytechnic until he took early retirement in 1980."

Peter Worsley (1962)

"Terence G Miller led a field trip to Arran in September 1962 for four of us who were about to start the study of Geology as one of our Principal subjects. Helped no doubt by the beautiful place and the excellent weather, the field trip inspired in me a real love for Geology. Geology turned out to be a big part of my professional life and continues to be a source of interest and enjoyment. I admired Terence Miller as a man: with his distinguished war record, his role as a half colonel in the TA, his agility in the mountains, and his setting of high standards not just for his students but also for himself."

John Rea (1965)

"This is a controversial subject which is certain to bring different opinions reflecting both intellectual attitude and personal experience. Of those men attending Keele in the early 1950's very few had done their National Service before they arrived. Most of us had two years of service to do after graduation. There were some ex-military men who had come to University having been in the services following the end of the War but they were not part of this National Service program and, of course, there were a few who had served before 1945. John Moulton's father was one of them along with Tom Parry (RAF) and I believe Josh Reynolds (Indian Army). Some members of staff served during the war, including Sammy Finer, Paul Rolo, Frank Bealey and Hugh Leach. Certain universities particularly Oxford and Cambridge required service to be completed before going up, otherwise the choice was personal: go now or later. My recollection of how boys felt about this upcoming event as they approached 18 is that it had to be done so make the best of the situation Unfortunately for some the duty was rough. The Korean War did not end until 1953 and although I did not know anyone at Keele who was in that war, there were certainly men at Keele who were in Malaya in 1949 and later. Eddie Underwood (1954) and Michael Daly (1955), both close friends of mine, had traumatic experiences in the Malayan jungles. I believe that Clive Collier (1954) was also in Malaya. Others, after completing their basic training, had very boring but safe situations and were just waiting for the day of release. Those who went after graduation had more opportunities for a more productive and interesting time. Several were commissioned and many others went into the Royal Army Education Corps, which counted towards their service for pension and seniority as teachers.

My brother in law, John Turner (1954), spent most of his National Service in Malaya teaching children of British military personnel. I am not convinced that everyone was exposed to mixing with men from different backgrounds. My own experience of such variety was limited to the first two weeks of basic training after which the first segregation took place, separating potential officer recruits from the rest. I do remember being asked by a young man from Suffolk during the first week of training if I would read a letter from his wife to him - obviously she could write but he could not read. Arthur Richardson (1954) and I arrived at Eaton Hall OCS in the same intake. He came from the Royal Artillery and I had been in the East Anglian Brigade, which was a pleasant coincidence for us. We shared the Chinese bedroom in Eaton Hall for most of our time there and were both commissioned in the South Staffordshire Regiment in May 1955. Arthur stayed with the Regiment in Europe while I was seconded to The King's African Rifles in Kenya, where I spent a very interesting 15 months initially as a platoon commander then as Battalion Intelligence Officer until returning to England in August 1956. I won't pretend that this was either dangerous or boring. Although the 'Emergency' did not officially end until sometime after I left there was more danger from wild animals than Mau Mau where I was stationed. Rhino and especially buffalo were a constant threat and we had some fatalities from these encounters. I spent the last three months of my time in East Africa in the Masai Mara on the Tanzanian border purportedly on a military mission but in fact it turned out to be a free safari in an area which had been a major game reserve but was at the time closed to all civilian activity due to the presence of terrorist gangs. So there it is, I learned Swahili and was paid an extra 5 shillings a day for my trouble and had a great experience as well. For me National Service was a big plus in terms of my own development and in my career and I am grateful for the advantages which Keele gave to me in making the most of this experience."

David Jeakins (1954)

"I came up to Keele after National service and was probably a better student for it, more mature and a bit more street wise than some of my fellow threshers. I agree with Martin Tunnicliffe that National Service was as important an experience as school or university for me in later life. I wanted to go into the army partly as a break from studying and partly because I wanted to get it over with. I joined the Royal Signals in September 1954, and endured basic training at Catterick, on the north York moors. It was very cold that year and we were treated as badly as can be imagined, running round the parade ground in full armour, up at 5.30am, and shouted at all the time. Some poor lads couldn't get used to wearing hard boots and their feet used to bleed profusely. In those days Catterick used to be featured in the national dailies every so often for its generally brutal regime. After four weeks of hell, during which I would cheerfully have murdered several of the corporals and sergeant I did six months wireless training. Then having asked to go to Cyprus or Austria, I was sent to Germany, which turned out well. I met some interesting Germans, among them an ex-submarine commander, but like Basil Fawlty, we did not discuss the war. As a result I became a lifelong Europhile, and I presently spend a lot of time in Europe. In 1954 Germany like Britain was coming out of wartime damage, and there were still many signs of destruction, even 10 years after the end of war. One of the shocks of National Service was learning that some young men could not read or write well. Several of them needed help from me to write home to their loved ones. Another experience for me was meeting some pretty tough guys from the Gorbals or Liverpool or Newcastle. They made pretty good soldiers, in fact. There were often fights on the weekends between the Brits, the Yanks and the Germans, due to drink or rivalry over the few girls that were around. Overall I enjoyed National Service and as you can imagine, I believe a year or so doing military or civilian service would be no bad thing for today's youngsters. Options and alternatives could be offered in educational, social care and environmental work, as well as military experience. At the end of our service we were concerned that we might be kept on, as Suez was just beginning to blow up. Fortunately I got to Keele in October 1956 and enjoyed it immensely. I remember listening to the debates there about the invasion of Suez, and to Professor Sammy Finer's contribution in particular."

John Dixon (1960)

"Those who came in 1950 numbered some former "real" soldiers (for example, one was a conscientious objector, had "dropped" at Arnhem to set up a field hospital before the main drop). Many former National Service representatives had served overseas, largely in Germany, and others had remained in the UK.. An implicit, albeit unspoken, "pecking order" of three bands developed. Strangely enough my memories of the undergraduate representatives are solely of those from the army. Amongst the largely young academic staff there was the first male warden, Robert Rayne, who had been a bomber pilot. His female counterpart, Mary Wilson, had occupied a senior position in the organisation of newly freed Germany. As the first four years moved on, other interesting persons joined us: one had grown up during the occupation of Guernsey and another had been, along with her mother, a prisoner of the Japanese. On the staff side, Ralph Elliott came still bearing the name the British Army gave to a young Jew whose family had wisely left Berlin in the 30's. He had been severely wounded as a tank commander in Normandy. We were also joined by a young US Air force officer who came to do Economics research whilst serving at Burtonwood. From the Deep South, he told tales of racism which were considered exaggeration at the time - now I'm not sure they were. Some were of the opinion that his position was less to do with academic research than to report back to Washington on what plots that very dangerous "Lefty", Lord Lindsay, was hatching. He befriended "Alf" (Usman Shah Abdullah al-Afridi) (1954), an Afridi from Afghanistan whose accuracy in handling a rifle was legendary. He told us that like his peers he was given a rifle on his seventh birthday and strongly encouraged to practise. He added the truthful observation that his tribe had severely defeated two attempts by the British Army to occupy Afghanistan at the end of the nineteenth century. The general opinion, it seemed to me, was that National Service was largely a waste of everyone's time but, for some, provided travel which our generation seriously lacked. It was also considered by many men that if it were to be applied then women should be so treated. But, it was like the rationing which we still endured, just something that had arisen and there were far more important things to do at Keele than debate National Service."

Bill Lighton (1954)

Photo above: Professor Sammy Finer

"Among those of the Staff who fought in World War II was W. B. (Bryce) Gallie, the first Professor of Philosophy, who was awarded the Croix de Guerre by de Gaulle for undercover services rendered in Holland after D-Day. One of his training companions was Lawrence Whistler, the glass engraver."

Anna Swiatecka (1954)

"By serendipity, I came across a cache of letters from Michael Lloyd, who taught English at Keele when I was there (1956-1960). They were to a friend and fellow-academic and poet, Alastair Macdonald, who taught English at Memorial University of Newfoundland until his death in 2007. They range from the 1940s, when they were both in the army - Michael Lloyd in Italy and Cyprus and Alastair MacDonald in India - to Michael's death about 1970. Michael Lloyd mentions that he has written two novels - and I remember seeing one, about Italy, I think. Does anyone remember the title? Was the second one also published?"

Roberta Buchanan (1960)

"Another pioneer who had served during the war was Josh Reynolds (1954). I believe that he had been a major in the Burma Army. Apparently, he still had a revolver with him at Keele. I was told that he would use cotton thread to attach ping pong balls to the branches of a tree outside his room window and use them for target practice after dark. Or was someone pulling my leg? Presumably, Fred Gallimore (1954) had been in the War too. Fred was married and lived off-campus. He was the first President of the Union. Ray Garner (1955), another mature student, left school at 14 with no qualifications and worked as a pot boy in the Potteries before the War. Having been wounded during his army service, he decided to become a doctor and came to Keele to read a science degree. I think there were special arrangements for ex-servicemen wishing to study in the immediate post-War years. That gave him the necessary academic qualifications to obtain a place in a London medical school but he had also used up his entitlement to state funding. So he worked his way through medical school, moonlighting between all the demands of medicine and earning his living. At Keele, he constructed a brick wall as his customized bedside table. Once, he invited me to coffee and served lukewarm "Milo" from a teapot. Quite a character and a successful medic."

Pam Lloyd-Owen (1954)

Photo right: Prof Bryce Gallie 1952

"I think Tom Long (1959) went to Kenya prior to coming up as he always said he wanted to return some time in the future. However most of the men in my year apart from those mentioned previously (John Shipston was in the RAF before Keele) were informed they would not have to do National Service before we went down in 1959 - so 1960 might have been cut off point for some but not all."

Dot Bell (Pitman) (1959)

"I have always said we were lucky to have a higher proportion of men who were that bit more mature when they arrived at Keele after National Service, and that it added something more substantial to our social experience. There seemed to be a notable change when the intake was straight from school - gap years not being a rite of passage in those days. On reflection to be truthful, I probably just liked having older men around. I do remember being very upset for one or two students who did National Service for four years after being at Keele and who found square-bashing desperately hard to take."

Anon

"My husband says you couldn't get drunk doing national service because you didn't have any money - he only got 15 shillings per week and if he wanted to go home that was it spent! He didn't learn any skills either only finding ways of how to get out of doing something."

Dot Bell (Pitman) (1959)

"When I arrived at Keele in 1956, I shared a room with Derek Edwards (1960). He had done his National Service (or equivalent) in the Air Force, as I recall as a navigator I had done mine in the Army, eighteen months of it as a second lieutenant (that lowest form of animal life) in the West African Frontier Force defending a far-flung outpost of the Empire. In what I think was our second term, Edwards and I came up with a scheme to form a territorial unit at Keele. This, I must admit, was not exactly dictated by patriotic motives. Rather it was because there was payment: for a two-hour gathering each week and for a two-week camp during the summer vacation. Warden "Oh Happy" Day kindly agreed to be the commanding officer, and we pinned up a notice in the beloved Nissen Hut Union seeking recruits. Alas, I wish I still had that notice which clearly demonstrated a lack of patriotic fervour among our cronies. Like "Joe Bloggs - Latrine Wallah" and "Mary Wilson - Highland Light Infantry" etc. Of the forty or so who signed, I think there was but one expressing serious interest. So ended Keele students' opportunity to fight for Queen and Country! On a more serious note, I think the virtue of National Service was that it offered a pause between school and university during which one could give more serious thought to what one wanted to study - not, say, Languages that the charismatic sixth-form teacher had encouraged one to pursue but Science or whatever. But then again, Keele's Foundation year served a similar purpose as well as introducing us to a broader range of disciplines."

Hugh Oliver (1960)

"On the matter of Pioneer students who came after National Service, my first hut roommate Rollo Wicksteed (1961) had been in submarines. As one with a horror of confined spaces, I was very impressed with his nerve. Antithesis!"

John Idris Jones (1961)

"It has always seemed to me that there are three distinct groups of men in our society: those who have been battle hardened on active service; those who have been trained in the armed forces without being actually involved in battle and those who have lived entirely as civilians. Until National Service ended, all men in the country - and hence at Keele - came into one of those three categories. This was obvious amongst our pioneers at Keele although almost impossible to describe. There is also a similar gulf in experience and attitude between those who lived through the War and those who have experienced only peace at first hand." Pam Lloyd-Owen (1954)

"They Almost Served"

"All I remember was getting a letter from the War Office one Spring morning as I was queuing for breakfast in Keele Hall to be told that Her Majesty didn't need my services to defend the realm and that I didn't really need to turn up at Catterick camp in September. It also said that the 20 injections I'd already had would be good for me."

Ticker Hayhurst (1960)

"As I understand it things were different for the select few that did national Service in the Royal Navy. The daily rum ration was still alive and well!"

Clive Sims (1967)

"Now National Service is called 'going to uni'. It is an open question whether there is any difference in alcohol consumed and skills learned."

Jim Thompson (1968)

I am pleased to let you have some memories of the United States Army being encamped on part of the Keele estate during the war. My sighting of General Patton outside the Clock House addressing a group of officers, being one of them. Of course I was very young at the time. I was evacuated from London to Keele at the beginning of the war in 1939 when I was three and a half and subsequently adopted by Mary and John Goodwin at the age of nine. John Goodwin was the Agent for the Keele Estate, with the estate offices situated within the Clock House close to Keele Hall.

The troops occupied Keele Hall and part of the Clock House too. The landowner, Colonel Ralph Sneyd, was not in residence, having lived for some years in Codford, Wiltshire.

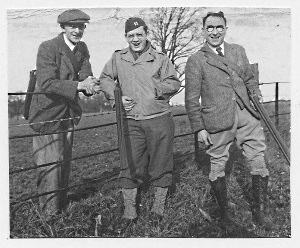

I was able to watch General Patton 'in action’ addressing a group of officers (wearing pearl handled pistol) outside the Clock House during his visit to Keele and several other American Army camps. My parents often entertained a number of American army officers during their time at Keele and my mother wrote to General ‘Ike’ Eisenhower to say how charming the US soldiers were. Ike was kind enough to reply even though he would probably have had one or two other matters on his mind at that time (1943)! I still have the letter. My father often invited those interested to join him on shooting and fishing expeditions on the estate that was replete with ideal terrain and several well-stocked lakes.

I have a clear memory of the locations of sentry positions at the main estate/camp access points. There were two along the road leading from the village to the camp, the first situated immediately opposite Keele Lodge, which was our home until 1943 when we moved one and a half miles out of the village along Whitmore Road to 'The Gables', a larger house adjacent to what had once been the Sneyd’s race course.

I was issued with an official ‘Pass’ that gave me access to the Clock House and a ride home in my father’s car. This meant that after the move, I had to walk through the camp where, on many occasions such was the generosity of our American cousins I was often given armfuls of ‘candies’. On the way I walked with tanks, army vehicles and other ordnance interspersed between the trees to the right and left of me lining the road and offering a fair degree of camouflage. The sentries got to know me and often waved me through without checking my Pass. However, one day I became careless and arrived at the second sentry box to be confronted by a new guard who I did not recognise me. I had left my Pass at home. No explanation was accepted and I was marched briskly over half a mile to the Clock House and up the stairs to my father’s office where the authenticity of my garbled story, thankfully was confirmed. Suddenly the hitherto severe face of the sentry was wreathed in smiles as he joked with my father.

Together with my father I was thrilled to be invited to have a ride in either a Sherman or a General Grant tank. I remember the ease with which the tank driver flattened a few quite large trees that we encountered.

A stray black Labrador dog followed my father from the camp to his office. He slept in front of the electric fire before wandering off again. The next day he could be seen lining up with the soldiers outside their Mess tent. My father stopped the car and the dog left the soldiers' meal queue and ran to him. The performance was repeated. The next day I was actually in the car when I witnessed the same ritual. The dog, again in the queue, saw the car and ran towards it, jumping in with complete confidence. Against the initial protestations of my mother, the dog was subsequently adopted by us and became known as ‘Flick'. He lived with us until he died in 1953. The sight of a dog queueing for his lunch until he saw the opportunity to get a better one was memorable!

John Goodwin American Officer Courtney CampbellIn one of the estate workshops, then called the Brew House, I met my first German who was of course, one of the prisoners of war working on the estate.

When the British Army was encamped on the estate remain, The Estate Offices were housed to the western side of the Clock House, now the University Music Department. My father's office was upstairs, overlooking the steep steps to the terrace that in turn overlooked the market gardens then run by a Mr Wales. A young clerk named William (Billy) Bedson and several office girls occupied the downstairs area. A Mrs Rogerson was the Keele Estate Company Secretary and was present as were my father and the girls when, as you will have read, General Patton stood immediately outside the offices and addressed a large group of soldiers. Mr and Mrs Rogerson moved into the Lodge after we had moved a mile and a half along the Whitmore Road to The Gable House adjacent to Racecourse Farm. Some American officers were housed within the south eastern part of the Clock-House.

When the British Army was encamped on the estate remain, The Estate Offices were housed to the western side of the Clock House, now the University Music Department. My father's office was upstairs, overlooking the steep steps to the terrace that in turn overlooked the market gardens then run by a Mr Wales. A young clerk named William (Billy) Bedson and several office girls occupied the downstairs area. A Mrs Rogerson was the Keele Estate Company Secretary and was present as were my father and the girls when, as you will have read, General Patton stood immediately outside the offices and addressed a large group of soldiers. Mr and Mrs Rogerson moved into the Lodge after we had moved a mile and a half along the Whitmore Road to The Gable House adjacent to Racecourse Farm. Some American officers were housed within the south eastern part of the Clock-House.

Photo right: John Goodwin (L) organised a shooting party at the Keele estate with an American Officer and local dentist, Courtney Campbell (R).

With regard to any experience of British soldiers I might have seen at the Camp, I certainly remember their presence before the American troops arrived in 1942. My only hands-on experience that remains with me is the occasion when my father and I were invited by two British soldiers to climb on board a Bren Gun Carrier. Not surprisingly at the age of about seven this was a most exciting experience. Interestingly our adventure was not limited to being driven around the camp that was only the start of it. I believe we were driven through the streets of Silverdale before returning to Keele.

As far as Commonwealth military personnel at Keele, I have checked the seventeen autographs that they wrote for me and find that Lieutenant Savides came from Nicosia, Cyprus; I remember him coming to dine with us on several occasions in 1942/3.

Photo below: Greek officer Lt Savides, Mary Goodwin and Jeff Goodwin in the garden at The Gables.

There was also a Captain Shefket, I believe Egyptian. One more story that might be of interest is that when I was seven or eight, I was walking home along Whitmore Road (one and a half miles) towards The Gables to which we had moved, and was joined by two young soldiers at the junction with the Two Miles Lane. Although they were friendly I was very nervous. I stared hard at their shoulder flashes. There had been one or two reports of assaults on children at that time. Eventually, to my great relief they turned back towards Keele. When I ran into the house I told my parents that "two soldiers from PLASTICINE had walked with me." My mother burst out laughing and explained that they were in fact Palestinian soldiers. Of course they had been absolutely charming!

There was also a Captain Shefket, I believe Egyptian. One more story that might be of interest is that when I was seven or eight, I was walking home along Whitmore Road (one and a half miles) towards The Gables to which we had moved, and was joined by two young soldiers at the junction with the Two Miles Lane. Although they were friendly I was very nervous. I stared hard at their shoulder flashes. There had been one or two reports of assaults on children at that time. Eventually, to my great relief they turned back towards Keele. When I ran into the house I told my parents that "two soldiers from PLASTICINE had walked with me." My mother burst out laughing and explained that they were in fact Palestinian soldiers. Of course they had been absolutely charming!

I feel sure that the young German prisoner who I met and got to know in the workshops at what was then known as the Brew House (by what is now Freshers' Gate) was from the Madeley POW Camp. We had fun playing our harmonicas together (mine was but a very simple mouth organ) and when he was repatriated at the end of the war, he left me his far superior Hohner.

In a letter dated 28th April 1945, from Brigadier Guy Gough, formerly Colonel in Command of 1st Brigade Of Royal Irish Fusiliers. 'In June 1940, after Dunkirk, you were most kind to us in every way, and to me in particular about fishing.' I also have a letter from General Eisenhower written to my parents in 1943 thanking them for their hospitality towards the Americans.

By Jeff Goodwin